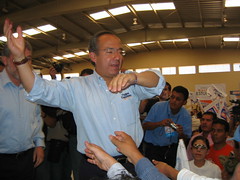

President Felipe Calderón at an April 2006 campaign rally in Tepatitlan de Morelos, Jalisco.

David Agren | 16 Jul 2008

MEXICO CITY -- President Felipe Calderón spent the week leading up to the second anniversary of his narrow election victory July 2 touring Southeastern Mexico, where he promoted the main tenets of his administration: security; structural reforms; and social programs.

While inaugurating a baseball stadium in Cancún that was built with funds from a public security program, he spoke of the Mexican military destroying a "world record" amount of cocaine and seizing more than 16,000 weapons over the past year.

The president also got his hands dirty mixing cement in a Campeche home as he promoted "Piso Firme," a program for replacing dirt floors in some of the country's most impoverished dwellings with more solid surfaces.

Upon returning to Mexico City, he spoke glowingly of his government's efforts at ushering structural changes -- especially its proposed energy reform legislation --while addressing an audience of bankers.

Calderón barely won the July 2, 2006, presidential election, garnering a scant 35 percent of the popular vote. Five months later, he barely managed to take the oath of office as left-wing lawmakers attempted to disrupt the ceremony.

But Calderón effectively put the close election behind him even as his scorned opponent, Andres Manuel López Obrador, declared the vote fraudulent and assumed the mantle of "legitimate president."

Calderón started his six-year term by declaring war on narcotics trafficking gangs and dispatching some 30,000 troops to hunt them down. He also reeled off a string of legislative accomplishments -- something his predecessor. Former President Vicente Fox, was unable to accomplish -- by striking deals with the Institutional Revolutionary Party, PRI, on overhauls to the state workers' pension plan, tax collection and the criminal justice system.

He even borrowed a page from López Obrador, whom Calderón had previously branded, "A danger for Mexico," and accused of advancing a populist agenda culled from the worst days of PRI rule. When tortilla prices climbed last year and public opinion turned against a proposed gasoline tax, Calderón resorted to the populism he decried in the 2006 election campaign by freezing prices.

His public approval rating soared in the first year, hitting 64 percent in December, according to a Grupo Reforma survey. Calderón even quelled the rebellious factions in his National Action Party, or PAN, by having a close confidant, Germán Martínez, run unopposed for the party presidency that same month.

Jeffrey Weldon, director of the political science program at ITAM, a private university in Mexico City, attributed the high approval ratings to Calderón's ability to pass reforms and his committing fewer self-inflicted injuries than Fox.

"People are giving him credit for trying to get things done," Weldon said.

As with many presidents, however, governing became more difficult during Calderón's second year in office.

His job approval ratings remain high: A June Consulta Mitofsky poll gave him 61 percent support. But Calderón has encountered stiff opposition to energy reform proposals that would allow expanded private sector participation in the state-run petroleum sector -- a sensitive topic in Mexico, where many consider public oil ownership to be a key pillar of the country's sovereignty.

Other second-year challenges include combating rising food and fuel prices that threaten to diminish the purchasing power of millions of Mexican households and confronting public opinion polls that reflect an increasing pessimism over the viability of the president's war on drugs.

ENERGY REFORM FIGHT

Winning passage for energy reform has perhaps been the most vexing for the president. Analysts say the issue was supposed to be a crowing achievement that Calderón and his party could campaign on in the July 2009 midterm elections.

Calderón geared up for the introduction of energy reform by appointing his most trusted ally, former chief of staff Juan Camilo Mouriño, as interior secretary in an effort to improve relations with Congress. He also tried taking advantage of internal chaos in the left-wing Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, which opposes any private sector involvement in the energy sector, and a seeming willingness by the PRI to once again broker a deal.

But few of the president's intentions for energy reform unfolded as planned.

Mouriño quickly encountered problems when López Obrador produced contracts suggesting the interior secretary had steered Pemex contracts to family businesses while working in various public positions.

A legislative commission cleared Mouriño of any wrongdoing, but his role as a liaison with opposition legislators was damaged.

After the reforms were unveiled in early April, left-wing lawmakers shut down Congress for 16 days. The shutdown derailed the possibility of approving energy reform before the regular legislative session ended April 30.

The Senate then embarked on a marathon series of 22 debates -- a condition that PRD, Labor Party and Convergence party lawmakers set for abandoning their protest -- in which energy reform is discussed by invited experts, activists and academics.

Pollster Jorge Buendía, director of Ipsos Public Affairs in Mexico City, said the initiative has now slipped away from the government as talk of a PRD-sponsored referendum on the issue generates more headlines than the content of the energy reform proposals.

Calderón responded to the legislative delays and decline in support for energy reform by sacking PAN Senate leader Sen. Santiago Creel -- an old adversary who was defeated by Calderón during the PAN presidential primaries and linked to a rival faction of the party.

Buendía said the changes reflected a crisis for the governing party and indicated a Calderón effort to take control of his party and tighten his inner circle.

"I can't remember a time when a [party] national executive committee removed a parliamentary leader," he added.

Creel had gained a reputation for being too accommodating to opposition demands, but his rivals in the Senate rebuked his forced departure, saying that a government that barely scraped into power and holds only pluralities in Congress is in no position to dictate terms.

"A government with an electoral minority, with a minority in Congress, being relentlessly hounded the left, can't use a heavy hand to impose its conditions," said Sen. Carlos Navarrete, PRD leader in the Senate.

A WORSENING ECONOMY

Issues beyond Calderón's control -- most notably deteriorating economic conditions and rising prices -- also have also been provoking headaches.

"They have an economy that's going down, inflation that's going up. None of this is any of their doing," said Federico Estévez, also a political science professor at ITAM.

He added that similar problems afflicted the Fox administration during its second year -- and contributed to PAN losses in the 2003 midterm elections that left Fox a lame-duck president.

Calderón has responded to the rising prices and economic turbulence with a number of measures, many of them emphasizing government intervention in markets.

Last month, he eliminated tariffs on wheat, corn and rice entering the country. At the same time, however, he froze the prices of 150 household staples ranging from beans to soap.

The president additionally defended subsidizing gasoline and diesel fuel by nearly $20 billion this year -- something U.S. motorists crossing into Northern Mexico have been increasingly taking advantage of.

Grupo Reforma columnist Sergio Sarmiento described the president's unwillingness to lift fuel subsidies as cosmetic measures that fail to help the poor and populist pandering that surpassed the actions of previous governments.

"Not even the [Mexico City] government of López Obrador had populism so pure," he wrote last month.

The president's economic populism and maneuvering toward establishing tighter control over his party represented a return to old-style PRI politics, said pollster Dan Lund, president of the Mund Group in Mexico City.

"It's a presidential system and he's moved toward basically the old PRI style: It's populist in its economic programs for the poor and its top-down," Lund said.

"The one successful model of the past -- successful in quotes -- is the PRI. No one is inventing a new model here."

A RETURN TO SECURITY FOCUS?

Calderón started his administration by implementing a law-and-order agenda and promising to rein in narcotics trafficking gangs. But his sending the military into troubled areas has resulted in a growing number of human rights complaints and failed to stem a rising number of drug-related deaths -- especially among police officers.

Public sentiment has turned against his war on drugs, which has claimed more than 1,600 lives in 2008. Two June polls showed that the public overwhelmingly believes that narcotics traffickers have gained the upper hand.

Ironically, Estévez, the ITAM political science professor, said the president could possibly win back some political capital by focusing once again on security.

"He has to put the military cap back on [and] wear the medals," Estévez said.

"That's the best thing going for him."

David Agren covers national affairs for the The News in Mexico City, where a version of this article originally appeared.

No comments:

Post a Comment