By David Agren

The News

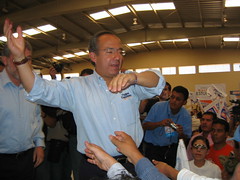

Germán Martínez Cázares, a staunch supporter of President Felipe Calderón, assumes the presidency of the National Action Party, or PAN, on Dec. 8.

Officially, the 40-year-old former federal comptroller will head the governing party for the next three years and lead it into the crucial 2009-midterm elections.

Unofficially, his ascent will sideline the party’s conservative-minded old guard, which has frequently bickered with the president and enjoyed little electoral success over the past year.

Martínez’s rise to prominence also marks a victory for Calderón and his pragmatic stream of the PAN as the president finally wrests control of his center-right party away from his detractors in the PAN’s conservative-leaning Catholic wing.

“It puts someone in who is close to the president,” said Jeffrey Weldon, a political science professor at ITAM, who noted Martínez’s moderate political views.

CLEANING UP AFTER ESPINO

Martínez inherits a badly divided party rife with ideological and personality-driven feuds that has sputtered of late in state and local elections – most notably in Yucatán and Aguascalientes, where conflicts over candidate selection and forging alliances doomed PAN campaigns in traditional party strongholds.

And his party presidency, which ushers in a younger generation of leadership, comes at a time when the PAN is making the difficult transition from being an erstwhile opposition fighting the previously entrenched Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, to establishing itself as the governing party.

Martínez succeeds outgoing president Manuel Espino, a polemic figure identified with the PAN’s conservative-Catholic wing, whose term as party head ends three months earlier than scheduled. Espino frequently squabbled in public with Calderon, who represents a more moderate and pragmatic faction that until recently was not well-represented in the PAN leadership.

“[Espino] created this view of a divided PAN,” Weldon said.

The tension between Espino and Calderón dates back to before Espino became party president in 2005, when Calderón endorsed a rival candidate for the PAN's top position.

Later, the Espino-led party hierarchy, which included former president Vicente Fox, openly supported former interior secretary Santiago Creel for the PAN presidential nomination and never enthusiastically backed Calderón’s presidential bid.

Calderón responded to the lack of support by branding himself “the disobedient son” during last year’s campaign.

CALDERON’S COUP

Calderón and Martínez share many similarities, dating back their modest upbringings in Michoacán and later advancements into the upper echelons of the PAN.

“They’re both very much the same kind of person in terms of who they are and where they come from and what they’re seeking,” said Federico Estévez, a political science professor at ITAM.

Both men hail from from lower middle class backgrounds and were mentored by Catholic academic and former PAN stalwart Carlos Castillo Peraza. The pair, both self-starters, also climbed the ranks of the education system, won two terms as federal deputies, served in high-level party positions and showed sharp political instincts for advancing to the top and “staying there,” according to Estévez.

Martínez also brings less baggage to the PAN presidency than Espino, who claimed the party’s top job under cloud of controversy after being accused him of rigging the party leadership vote and employing corporatist practices during the contest.

Espino, who won with Fox’s backing, took active interest in the selection of local candidates, taking advantage of the influence wielded by the presidents of Mexico’s political parties.

“[Party presidents have] a lot of discretionary power,” Estévez said.

“You can’t get anywhere without the [party] president coming onboard.”

Relations further soured with Calderón after the July 2, 2006, when, according to Mexico expert George Grayson, “Espino became a thorn in the side” of the recently-elected president.

Grayson, a government professor at the College of William & Mary, said that Espino appointed PAN leaders in the new Congress affiliated with the party faction hostile to the president and dithered over forming an alliance with the PRI in last summer’s Chiapas gubernatorial election, which was narrowly captured by the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD.

Espino’s tough approach to leadership also dismayed many in the PAN as internal conflicts dominated the headlines during his term. The federal Electoral Tribunal recorded complaints from 1,530 PAN members over the past year regarding the infringement of their party privileges – some 77.5 percent of all grievances filed.

It also led to mixed electoral results. The PAN successfully maintained its grip on the presidency and captured record pluralities in both houses of Congress in 2006 – accomplishments Espino frequently points out. But the PAN suffered some embarrassing losses in state and local contests afterwards, which Martínez addressed when he announced his candidacy for party president on Oct. 29.

“If we continue losing municipal governments we risk losing the presidency in 2012,” he said at the time.

According to Aldo Muñoz, a political science professor at Universidad Iberoamericana, Calderón and Martínez champion a pragmatic, “neoPANista” wing of the party, while Fox and Espino allegedly lead a religious-conservative “doctrinal” branch, which is influential on the state and local level in Western Mexico and is often referred to as “El Yunque,” or The Anvil.

Martínez recognized the PAN schisms during a campaign rally in his hometown of Quiroga, Michoacán and promised to include members from both sides of the party in the party’s executive committee. He also noted the challenge of incorporating new members drifting over to the PAN due to its proximity to power.

But pollster Dan Lund questioned whether Martínez and Calderón would be able to unite the party around themselves going forward.

Lund noted that the PAN has long lacked the underpinning of a policy agenda, which has made it more vulnerable to internal disputes and power struggles.

“I don’t think anyone has forged policy leadership,” said Lund, president of the Mund Group in Mexico City.

“And when you don’t have a plan you tend to get bogged down in personalities and fiefdoms.”

No comments:

Post a Comment