22 December 2008

Peje holds garage sale

David Agren

The News

Rogelio Alcántara rose early Sunday morning to bake hundreds of loaves of bread from a scratch recipe calling for whole-wheat flour, oats, flax and sunflower seeds. The bakery owner from Coacalco, State of Mexico, hauled the bread to the capital's Colonia Roma, where the he set up a table at a garage sale organized by Andrés Manuel López Obrador and hosted in a warehouse adjacent to the abode that hosts the headquarters of the election runner up's "legitimate government."

The loaves sold briskly for 22 pesos each – not surprising since some López Obrador followers publicly loath the ubiquitous offerings from baked good giant Bimbo and mock the company on signage at "legitimate government" events. But Alcántara only pocketed the costs of baking the dense loaves and planned on donating the profits to the "legitimate government."

Alcántara was only one of the dozens of participants at López Obrador's garage sale, an event attendees said was an opportunity support the "legitimate government" while poring over an eclectic range of merchandise that ranged from an old typewriter to used clothing to a 1987 history of the National Polytechnic Institute's student movements – still in its original cellophane wrapping. But their generosity also addressed a real and potentially troublesome concern for López Obrador: Financing.

The garage sale was held as López Obrador's financing comes under scrutiny and some of his sources of monetary support have already disappeared. Other sources appear to be in jeopardy.

Already some lawmakers in the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, publicly said they would withhold voluntary monthly donations of up to 20,000 pesos that underwrite the former Mexico City mayor's shadow government and opposition movements in "defense" of the state-run petroleum industry and the deteriorating family economy.

It was also revealed in November that he had traveled to rallies free of charge via pay highways by using a loaned card that allows lawmakers to avoid paying tolls. And earlier in the year, allegations were made that money flowed from the various Mexico City boroughs into the leadership campaign of Alejandro Encinas, who López Obrador was backing for PRD president.

López Obrador's long-term financial prospects could also be hurt by his candidate's loss in the PRD leadership contest as rival factions will now control the party's finances.

Questions from other political parties are now starting to be asked. On Sunday, the Social Democratic Party, PSD, which had an apparent election deal with the PRD scuttled last weekend by López Obrador loyalists, demanded an investigation in to López Obrador's finances. PSD president Jorge Díaz Cuervo said Sunday that his party would demand a Federal Electoral Institute, or IFE investigation since López Obrador could use his various movements to promote loyal political candidates in the 2009 midterm elections. The PSD estimates that the "legitimate government" operates on a monthly budget of between 5 and 6 million pesos.

Despite the controversy, some income sources have been unwavering. Many lawmakers in the FAP coalition of left-wing parties plan on maintaining their monthly donations and planned on turning over a portion of their Christmas bonuses to "López Obrador."

The "legitimate government" claims that it has signed up 2.2 million members since being formed in 2006. Some of its members, like Chalco, State of Mexico resident Ignacia Martínez López, are also unwavering.

"We came to support [López Obrador," she said while toting a bag brimming with used clothes – and loaves of bread.

13 December 2008

What's Next for Andrés Manuel López Obrador?

The second anniversary of President Felipe Calderon taking power passed earlier this month - along with the second anniversary of the "gobierno legitimo" being founded by election runner up and the self-proclaimed "presidente legitimo" Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

World Politics Review ran a pair of good analysis pieces:

Mexico's Calderón Faces More Obstacles Ahead (By Patrick Corcoran) and What's Next for Andrés Manuel López Obrador? (By David Agren.)

26 November 2008

Deputies dispute plan for overhauling police

by DAVID AGREN

The News

Opposition lawmakers on Tuesday rejected proposals for creating a single federal police force under the command of the Public Security Secretariat, or SSP, but signaled their willingness to back other safety measures proposed by President Felipe Calderón.

"We don't want to see a single police force," Deputy Francisco Rivera Bedoya, the president of the Public Security Committee and a member of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, told The News. "We want to see better coordination between [all of the forces] rather than a single federal police force."

The opposition to the policing proposal will mean more delays on security measures proposed this summer. Lawmakers will likely miss a Saturday deadline for achieving the 74 public security objectives laid out at an August federal crime summit.

Lawmakers on Tuesday expressed little discomfort over missing the deadline, however.

"Our commitment is to introduce legislation during our normal period of sessions, which ends Dec. 15," said Senate president Gustavo Madero.

Since the summit, Calderón has presented measures that would change sentencing laws, target the assets of those affiliated with organized crime, crack down on kidnapping and decriminalize the possession of small quantities of drugs.

He also proposed revisions to the National Security System Law, calling for the merger of the Federal Preventive Police, or PFP, and Federal Investigations Agency, or AFI, and proposing the new force be granted broader preventive and investigative responsibilities. But the country's two main opposition parties - the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, and the PRI - almost immediately voiced objections.

On Tuesday, PRI lawmakers objected to increasing the budget for the federal police at the expense of the state forces, as well as the creation of a more powerful SSP led by Public Security Secretary Genaro García Luna. The PRD also objected.

Members of Calderón's National Action Party, or PAN, backed the measure, saying it would improve local police.

"We have 2,438 municipalities with police forces, 32 [states and districts] with police chiefs, plus federal forces," PAN Dep. Edgar Olvera, the secretary of the Public Security Committee, told The News. "We're a country with a large number of police forces, but without a law for coordination and cooperation."

Olvera also discarded PRI complaints that reducing money for local police forces is "violating state sovereignty," saying that the PRI is using that argument to evade accountability. The PRI currently governs 18 states and its governors wield enormous influence within the party.

"The state governors - the majority of them PRIístas - want to receive the money," Olvera said. "They all want to receive the money, but they don't want to accept the rules. They all want to have discretion with the resources."

20 November 2008

The next step in the López Obrador show

By DAVID AGREN

The News

Two years ago, an estimated 300,000 of Andres Manuel López Obrador's supporters packed the Zócalo in Mexico City to witness the anointing of the nation's "legitimate president." A year on, about 100,000 gathered there for his first "Informe" - his version of the president's state of the nation address.

This Thursday, López Obrador will once again rally the masses for an address. But he's not calling it an Informe - analysts say that's a reflection of the public having moved past the contentious 2006 election - and he won't be speaking inside the Zócalo, instead opting for a space nearby. Few expect turnout to be in the hundreds of thousands.

More than two years after the controversial 2006 election, López Obrador is soldiering on with his staunch opposition to the Calderón administration. And many of his loyalists - and some analysts - still see López Obrador as the nation's only true opposition leader and the most important figure in the Mexican left.

But Nov. 20, the anniversary of his "legitimate government" arrives on the heels of several setbacks for López Obrador. The energy reform package he tirelessly crusaded against was approved in Congress, and this past week, the Federal Electoral Tribunal, or Trife, quashed the aspirations of his preferred candidate for the leadership of the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD.

Now, instead of trying to establish himself as a political force, the "legitimate president" is simply seeking to stay relevant in the public policy discourse, as well as capitalize on new crises like the deteriorating economic situation. Some see his trajectory as beyond his control, given how difficult it will be to set his own agenda in the face of an economic downturn, among other powerful forces.

"His future doesn't depend on him at this stage of the game," said ITAM political scientist Federico Estevez.

STAYING IN THE GAME

López Obrador has struggled to find relevance since assuming the "legitimate president" mantle.

Two years ago, he outlined a 20-point plan for rescuing the country. He borrowed heavily from the populist proposals of his presidential campaign, and later set out on a tour of the nation's municipalities to spread the message and denounce supposed electoral fraud.

His movement failed to gain much traction in the first year, as few media outlets followed him off the beaten path. In the meantime, Calderón achieved several major legislative victories.

In his Informe last year, López Obrador delivered a 2008 forecast of economic hardships brought about by rising prices and stagnant incomes. But his message was overshadowed by the actions of a small band of renegades who stormed the Metropolitan Cathedral to protest the usual ringing of the church's bells.

Events beyond López Obrador's control would continue to haunt him through much of 2008, although his tactics, at times, appeared to be inspired. The legitimate president suspended his nationwide tour to oppose energy reform proposals that would have allowed for greater private-sector participation in the government-run petroleum sector. He organized brigades of protesters, and loyal lawmakers shut down Congress for 16 days to prevent debate after Calderón presented his proposals. The buzz surrounding a July referendum on energy reform, sponsored by PRD factions loyal to López Obrador, even supplanted discussion of the actual proposals.

But then the agenda shifted abruptly to public security.

López Obrador was left protesting an issue that much of the public had stopped caring about. And instead of proposing solid solutions for security, he clumsily tried linking the end of energy reform to the maintaining of law and order.

"We all want our children and grandchildren [to be able to] walk the streets free of fear," he told a crowd in the state of Guanajuato on Aug. 17. "Therefore, I propose the following: The first thing we have to do is avoid the privatization, open or disguised, of the national petroleum industry."

On the evening of Sept. 15, he spelled out a 10-point plan for saving the country from deteriorating economic conditions and public security woes. Barely an hour later, two grenades tore through Independence Day festivities in Morelia, distracting attention from his message.

By the time Congress actually voted on the energy reform proposals - which some PRD senators were instrumental in crafting - López Obrador's opposition and brigades of protesters storming the barricades had become mere sideshows.

BREAKING UP THE PARTY

Analysts, as well as some in the PRD, say López Obrador ironically helped shape much of the final energy package, but that his intransigence and unwillingness to compromise ultimately hurt his own party.

"The only thing that he has achieved is to give more power to the [Institutional Revolutionary Party] and minimize the PRD's political weight," said pollster Jorge Buendía, of the firm Buendía y Laredo.

"The level of rejection toward the PRD is of such a magnitude that those looking to cast a protest vote no longer see the PRD as an attractive option. They're going to the PRI."

The energy reform issue highlighted López Obrador's uneasy coexistence with the PRD.

Now, the electoral tribunal ruling has allowed López Obrador's opponents to seize control of the party. Its overturning of the annulled PRD elections - which were primarily fought over López Obrador's strategy of avoiding all dealings with the federal government - has been regarded as a major blow to his party status.

The PRD's National Executive Committee also recently took measures to distance itself from the pro-López Obrador coalition known as the FAP by cutting off funding for the coalition.

His electoral allies in the Convergence party and Labor Party - part of the FAP - have remained unwavering in their support. "He's the most important voice of protest in this country," Convergence party Deputy Jose Manuel del Río Virgen told The News. "He still has strength."

But public opinion - in the past, the main source of López Obrador's strength - is proving problematic. A September poll by Ulises Beltrán y Asociados found that 50 percent of respondents hold a negative opinion of López Obrador.

This Thursday, turnout will be yet another gauge of the "legitimate" president's legitimacy in the eyes of the public.

ECONOMIC SALVATION

After a year filled with protests on energy and the continuation of cries of fraud, López Obrador recently changed his discourse to economic topics, including rising prices for food and fuel, stagnant incomes and a lack of support for the countryside. While touring Michoacán last weekend, he blamed the country's economic woes on "Calderón's ineptitude."

And analysts are at odds over whether he can regain ground by focusing on such matters.

Some, like Aldo Muñoz at the Universidad Iberoamericana, say the shift from the fraud issue is a smart one. As it disappears from the public consciousness - "[people] care more about the present situation than they do 2006," Muñoz said - focusing on the present crises is more important for López Obrador.

The ITAM's Estevez said the issue actually favors the former presidential candidate, who has long been waiting for the Calderón government to stumble badly, or encounter a crisis.

"He was betting that the Mexican economy would sink, and now it turns out that it may sink because of the world," Estevez said.

"It's no longer an untenable strategic position."

19 November 2008

Encinas sticking with split PRD

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

Democratic Revolution Party leadership runner-up Alejandro Encinas ended speculation over his political future Tuesday, announcing his intentions to stay in the PRD.

He will continue leading a coalition of factions in the nation's largest left-wing party, he said, declining to take the No. 2 position in the party's National Executive Council.

The former Mexico City mayor, who was last week confirmed the loser of the PRD's March 16 presidency contest by a federal tribunal, had floated the possibility that he might split from the PRD after his rival and leader of the moderate PRD faction known as the New Left, Jesús Ortega, was declared the winner.

But on Tuesday, he expressed solidarity with his party, if not Ortega's part of it.

"We're not leaving the PRD; this is our party, the party that we founded . It's the result of decades of work," he told supporters in Mexico City.

Encinas also announced plans for a new social movement - not unlike the petroleum defense movement launched by his political patron, Andrés Manuel López Obrador - that he would fight to rid the PRD of problems that he said included patronage and increasing bureaucratization.

"We won't leave the party to those who have been entrenched in its bureaucracy. Far from staying in the trenches, we're going to fight from inside [the party]."

The fight could prove difficult. Ortega already controls much of the party infrastructure, and can now exert increased influence over the candidate nomination process for the 2009 midterms.

The Ortega strategy, which calls for the party to cooperate with political rivals and negotiate with the federal government, is also expected to become more common with his ascent to the PRD presidency.

Ortega takes office on Nov. 30, more than eight months after PRD members went to the polls in an election that was originally annulled due to widespread irregularities. Encinas' United Left, whose members allege that the 2006 presidential election was rigged, said that the same chicanery was rife in the PRD election. Encinas unsuccessfully petitioned for the results from disputed polling stations in Ortega strongholds to be eliminated from the final vote count.

The electoral tribunal known as the Trife sided with Ortega, however. Encinas rebuked the Trife on Tuesday for intervening in an internal party matter and once again making "a political decision" against his factions. He said that accepting the No. 2 PRD position would have validated the Trife ruling.

"I can't sweep this garbage under the rug and I don't want to be an accomplice to those that commit abuses and irregularities," he said. "[The ruling] is a coup against our party by an authoritarian and intolerant state."

Encinas' decision to stick with the PRD was not entirely unexpected, as it is too late to form a new political party for 2009, and leaving would mean giving up annual public financing of more than 400 million pesos.

17 November 2008

Anger grows over Chihuahua crime

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

Public outcry mounted in Chihuahua on Sunday as the wave of violence plaguing the northern state continued unabated, this time claiming a top state police commander.

A group that included 62 of the state's 67 mayors as well as business and university organizations and the bishops of three Chihuahua dioceses published an open letter to President Felipe Calderón on Sunday, urging him to overhaul federal crime fighting efforts in the nation's largest - and this year, most violent - state.

"We ask that you refocus Joint Operation Chihuahua and in general the strategies of combating organized crime," stated the letter that was published in newspapers throughout the state.

Hours before the letter's publication, yet another police official was murdered in the border city of Ciudad Juárez. José Manuel Sanginés Leal, regional director of investigations for the state police, was shot at 149 times while driving a police pickup truck, according to investigators. Police captain Miguel Carlos Herrera González was killed the day before by unknown assailants.

A crime reporter for the newspaper El Diario was also assassinated last week in the city.

Joint Operation Chihuahua organizes federal, state and local officials to battle organized crime in the state and is part of Calderón's efforts to crack down on trafficking cartels. Experts say the operation is failing to produce results because of problems with intelligence and an inability of federal and state officials to work cooperatively.

According to UNAM security expert Pedro Isnardo de la Cruz, Sunday's open letter sent the right message to Los Pinos.

"The system of coordination between federal and state authorities isn't trustworthy. The president has to do a top-to-bottom purge," de la Cruz said.

"The level of infiltration by the cartels into police forces and the infiltration into politics and governments is now, after Sinaloa, the highest [in Mexico]."

Chihuahua has been the scene of a bloody turf war between narcotics trafficking gangs, who have increasingly been turning their guns on local and state police - 59 law enforcement officials have been slain in Ciu-dad Juárez so far this year. Reforma estimates that the war on organized crime has claimed 1,368 lives in Chihuahua thus far in 2008, a sharp increase from the 147 deaths registered the previous year.

In response to the violence, increasing numbers of Chihuahua residents are acting or speaking out for change.

Last week, members of the state's 40,000-member Mennonite community shuttered business to demand an end to the violence. On Saturday, the state's opposition National Action Party demanded the resignation of Chihuahua's two top law enforcement officials.

One diocese in the southern part of the state has even gone as far as to deny funeral rites to narcotics gang members murdered for their criminal activities.

15 November 2008

Yunque bogeyman won't die

The News

In the aftermath of Mouriño's untimely death in the Nov. 4 plane crash that killed Interior Secretary Juan Camilo Mouriño, amid conspiracy theories of sabotage and drug cartel involvement, reports have emerged that a shadowy faction within the governing National Action Party known as "El Yunque," or the Anvil, was just as anxious to topple Mouriño.

"The Yunque was going to do everything in its power to destabilize the president" – which meant attacking Mouriño has a proxy – said former Puebla mayor and admitted ex-Yunque member Luis Paredes. Paredes added that the group was still smarting from being deposed from the party leadership by Calderón and his tight inner circle. Meanwhile, one of those deposed, Manuel Espino, denied that there had been a campaign to discredit and bring down Mouriño, saying it was the drug cartels who were the enemy, not The Yunque.

This PAN feuding in the press this past week has not only highlighted the divisions in the governing party, but also revived one of the oldest bogeymen in Mexico politics: The Yunque, a group characterized by staunch Catholic and conservative beliefs that reportedly has wielded enormous influence over the party throughout the past few decades – especially in the PAN heartland of Jalisco and Guanajuato.

But whether or not the Yunque even exists is disputed by analysts and members of the PAN – even if they won't deny that some in the party bring deeply religious beliefs and tilt sharply to the right.

"There are people [in the PAN] who are much more conservative than others," PAN Deputy Gerardo Priego told The News. "But this idea that they meet and bathe themselves in goats' blood, and do other strange things, is exaggerated."

The label, he said, "Is a way to easily tag adversaries."

Others, like PAN Deputy Obdulio Ávila Mayo, said the Yunque "exists," but not necessarily as a PAN-only group.

"Not all of the Yunque is part of the PAN, and not all of the PAN is part of the Yunque," he told The News.

ITAM political science professor Jeffrey Weldon said the Yunque label persists as way to describe PAN factions. The party's internal conflicts frequently simmer beneath the surface, but seldom erupt into the full-blown wars over wide ideological rifts, he said, due to the fact that the PAN's members share relatively similar core values.

Priego, a former National Executive Committee member from Tabasco state, who does not identify with the conservative factions of the party, expressed some discomfort with the use of the Yunque label – many non-Catholics are members of the PAN, he said, and in some states, they constitute a near-majority.

"In Campeche, half of the membership is Mormon," he said.

13 November 2008

Moderate named winner of left-wing party's elections

By DAVID AGREN

The News

The Federal Electoral Tribunal, or Trife, settled the Democratic Revolution Party´s internal leadership election on Wednesday, nearly eight months since party members cast their ballots for a president.

The decision gave three-time leadership candidate Jesús Ortega the PRD presidency, dealing a stiff blow to former presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who backed a rival candidate and now finds himself at odds over strategy with the new party hierarchy and lacking influence over the candidate nomination process.

Ortega, the leader of a moderate PRD faction known as the New Left, led the original vote count over rival Alejandro Encinas by some 16,000 votes, but the outcome was annulled after the committee charged with overseeing the election found irregularities in more than 20 percent of the polling station tallies. The election and leadership campaign were rife with allegations of improper campaigning, vote tampering and ballot boxes being stolen.

The Trife said in its ruling that enough of the polling stations had been installed to adequately stage the election. It also adjusted the final vote count, giving Ortega an even bigger advantage.

Encinas, who had been endorsed by López Obrador, rebuked the ruling on Wednesday, calling it "a clear intrusion by the state into the internal life of our party."

He said that the Trife ignored irregularities - votes from polling stations that were never opened were included in the final vote count, for instance - and called on Ortega to "not accept" the decision and to instead reach an agreement for governing the party.

Ortega wasted little time Wednesday in announcing that he would seek unity in his divided party, and also pursue dialogue with the federal government - a clear departure from the López Obrador strategy of eschewing all contact with and acknowledgement of the administration of President Felipe Calderón.

The New Left favors working cooperatively with other political factions, in contrast to the United Left, a coalition of factions loyal to López Obrador and Encinas.

PRD politicians loyal to Ortega also broke ranks with López Obrador over the energy reform issue last month, negotiating a deal with the politicians from other parties.

Encinas supporters on Wednesday also expressed their disgust with the Trife, a federal judicial body that referees internal party squabbles and electoral disputes - and which ruled against López Obrador´s claims of fraud in the 2006 presidential election.

11 November 2008

New No. 2 signals party push for unity

The News

With the sudden death last week of Juan Camilo Mouriño, President Felipe Calderón shelved his criteria for appointing Cabinet members on Monday, and reached beyond his inner circle to tap Fernando Gómez Mont as interior secretary.

Analysts say the move reflects a new style of governance being ushered into Los Pinos, and that the president is signalling his desire to advance his agenda of structural reforms in a divided Congress. This would require a shrewd negotiator and non-polarizing figure in the Interior Secretariat.

"This is a good signal because the president, governing with his inner circle, has been isolated and not really able to build bridges," said political analyst Jorge Zepeda Patterson. "Calderón's Cabinet [has been] characterized by people who have long futures, but short pasts."

The appointment also reached across current breaches in the National Action Party, or PAN, which has been plagued by low-level feuds between pro-Calderón groups and those that never warmed to his nomination for the presidency.

"[The appointment of Mont is] a strong signal for a unified party," said Jeffrey Weldon, a political science professor at the ITAM.

AN OLD HAND

Gómez Mont, the son of a PAN founder and close collaborator of former PAN presidential candidate Diego Fernández de Cevallos, brings a long political history to the Interior Secretariat. He previously sat in the Chamber of Deputies in the early 1990s and participated in commissions that revamped the electoral and judicial systems.

As a criminal defense attorney, he later defended both former President Carlos Salinas and the president's brother Raúl along with a former Pemex director implicated in the Pemexgate scandal.

He also helped create the tamper-proof voter identification card that most Mexicans carry in their wallets.

As an attorney, Gómez Mont developed a reputation as a shrewd negotiator - a key skill for an interior secretary, who acts as a liaison between the presidency and other levels of government, but who is also responsible for security matters.

"The main function of the Interior Secretariat is precisely that of a political operative," Zepeda said. "They didn't opt for a military man, or police official as many had speculated."

Mouriño drew posthumous praise for his political skills, but was derided through his 10-month term by left-wing lawmakers anxious to assail the president via a proxy. They demanded the interior secretary's resignation over allegations of previously steering business to a family company.

Zepeda said Gómez Mont would mostly like draw less fire, but could be "injured" by left-wing lawmakers who hold grudges against Fernández de Cevallos, a controversial figure for his decision to defend private companies as a lawyer against the government while serving as a senator.

"It's important for Calderón to be able to have a moderate left that is allied with him to pass reforms and not have to depend on the [Institutional Revolutionary Party]," Zepeda said.

10 November 2008

PRI dominates in Hidalgo

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

Early returns from the central state of Hidalgo showed voters solidly backing the Institutional Revolutionary Party in Sunday´s municipal elections.

The PRI and its election allies were leading in 50 of the 84 races; seven municipalities had yet to report returns. Notable results included the PRI leading in the capital, Pachuca, and the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, leading in Zimapán, where the leader of a civic group opposed to the construction of a toxic waste dump was running for the left-wing party.

Sunday´s results appeared certain to further cement the PRI´s hold on Hidalgo where it held 35 municipal governments on election day. The party swept all 18 directly elected seats in the state Congress during legislative elections earlier this year and holds the governor´s office.

Chicanery was also rife during the election period. The state Attorney General´s Office reported receiving at least 50 complaints of election-related incidents, including murder, improper police detentions and the enticing of voters with free rides and giveaways.

PAN officials in Pachuca alleged that four out-of-state election observers were detained and roughed up by local police. A Saturday confrontation between the PRI and PRD campaigns in the municipality of La Mi-sión resulted in a police commander being shot dead. Two PRI operatives - brothers of the local PRI candidate - were named as suspects in the shooting by state judicial authorities. Gunfire was also reported in the municipality of Huejutla.

Hidalgo, a small rugged state north of the Mexico City metropolitan area just beyond the State of Mexico, usually opts for the PRI, although it supported the PRD campaign of former Mexico City Mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador in the 2006 election and opposition parties had won a few municipal races over the past decade.

Analysts predicted the PRI would benefit in Sunday´s local elections based on its party unity and its well-oiled patronage machine while its opponents were suffering from disunity and disorganization.

07 November 2008

No funeral rites for narcos

A bishop in Northwestern Mexico recently rebuked the rampant narcotics cartel violence in his diocese by forbidding all 66 priests under his supervision from performing funeral rites for those killed in drug-related slayings.

"Given the circumstances of violence and death that we are living in our communities, I especially ask priests and those that preside over funerals to comply with what church law establishes and deny funeral rights to all those that noticeably and openly are part of a crime," Bishop Jose Andres Corral of Parral said during his Nov. 2 homily.

The Diocese of Parral covers the southern part of Chihuahua state, where a government crackdown on narcotics cartels has resulted in 1,287 deaths so far this year – 10 times as many as were recorded in each of the past two years, according to the Grupo Reforma newspapers.

Priests in the diocese appear willing to comply. Father Miguel Angel Saenz Vargas, a prelate in the municipality of Guadalupe y Calvo, the hub of a violent cartel-infested region known as the "Golden Drug Triangle," told the El Universal newspaper, "It's a contradiction, a scandal within the church itself that people, who led a life distant from God, upon dying have [the same] funeral rights as those of other faithful (people) that lived for Christ."

05 November 2008

Mouriño dies in crash

by DAVID AGREN

The News

The nation's highest-ranking Cabinet official died Tuesday evening when his government-owned jet plunged into a narrow street lined with office buildings in the capital's upscale Lomas de Chapultepec neighborhood.

Interior Secretary Juan Camilo Mouriño, a trusted adviser of President Felipe Calderón and the country's top public security official, died in a crash that claimed the life of José Santiago Vasconcelos, the former lead federal prosecutor for organized crime.

"Mexico lost a great Mexican, intelligent, loyal, committed to his ideals, honest and hard-working," President Felipe Calderón said in televised remarks Tuesday night.

The president tapped his former chief of staff to be interior secretary earlier this year in an effort to smooth relations with Congress for the introduction of a politically sensitive energy reform package. But the Spanish-born Mouriño, 37, immediately became polemic as contracts surfaced suggesting that he had steered Pemex business to family businesses while serving in previous public positions. He was most recently mentioned as a possible gubernatorial candidate in his home state of Campeche.

Mouriño and Vasconcelos were returning from public security meetings in the state of San Luis Potosí, but their plane crashed for reasons that are still unclear to investigators.

The crash killed all nine passengers and crew members and at least three more on the ground, according to Carlos Huber, spokesman for the civil protection agency in the borough of Miguel Hidalgo. At least 40 people were injured, seven of them seriously.

Photos taken by Huber shortly after the crash showed at least three weapons belonging to passengers on the plane littering the scene.

He told The News that at least 20 vehicles were torched and one of the victims was found sitting in a car.

Huber said that the Learjet 45 appeared to have been traveling in a northward direction - the opposite direction for aircraft arriving in Mexico City from San Luis Potosí and contrary to the normal flight path to the capital's international airport.

31 October 2008

The politics of energy reform: assessing the winners and losers

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

All sides in the energy reform debate lauded themselves for accomplishing what had been politically unthinkable a decade ago – and promptly took credit for the approval of a seven-point package that overhauls the state-run oil concern Pemex and allows for increased private sector participation in the petroleum sector.

President Felipe Calderón called the approval of an energy reform package the most import event in the country’s petroleum sector since March 18, 1938, the day foreign oil companies were evicted from the country by then-President Lázaro Cárdenas. Senior officials in the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, and Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, made similar pronouncements, but also highlighted their roles in hammering out an agreement that took more than six months to achieve and involved a 16-day takeover of Congress by left-wing protesters, more than two months of hearings over the summer, a partisan referendum and street protests.

Even ardent energy reform foe Andrés Manuel López Obrador claimed some responsibility for his role in forcing lawmakers to water down the original proposal as he told supporters of this petroleum defense movement that their threats, legislative shutdown and street protests resulted in plans being included for a new refinery - to be built with public money - and changes to some of the company’s accounting rules.

But the self-described “legitimate president” rebuked the final reforms due to the lack of a clause forbidding the exclusive management of specific geographic areas by foreign companies.

PRI THE BIG WINNER?

López Obrador aside, analysts say each of the three big parties won something through energy reform, but perhaps none as much as the PRI.

“The big winner in this is the PRI because its legislative agenda and political agenda is embodied in the final documents,” said Aldo Muñoz, political science professor at the Universidad Iberoamericana.

The PRI, which held the chair of the Senate Energy Commission, unveiled a middle-ground proposal that gained wide acceptance. It proposed scrapping plans for private investment in refineries, storage and pipeline maintenance and discarded the idea of setting up smaller Pemex subsidiaries.

PRI legislators also stayed united throughout the energy reform process, having pacified its more nationalistic factions in the Chamber of Deputies, and protected one of its biggest patrons, the powerful oil workers' union.

“[The union] is a PRI partner and with the PRI winning, the union also wins,” Muñoz said.

Somewhat ironically, some analysts say the deal brokered in Congress contains similarities to a proposal that intransigent PRI lawmakers shot down earlier this decade.

“The least common denominator that we have now is the one that we had several years ago. Everyone agreed that Pemex needed an administrative and a financial reform, that’s what it has,” said Federico Estévez, political science professor at ITAM.

“Four years ago it was impossible because the PRI was unwilling to play ball.”

ANOTHER PAN ACHIEVEMENT

President Felipe Calderón took pains to point out that approval of an energy reform package marked the fifth major reform to come out of a divided Congress during his administration. Other reforms included changes to state pensions, tax collection, the electoral system and the criminal justice system.

The path to achieving energy reform took a toll on the governing party, however. Calderón appointed his most trusted adviser, Juan Camilo Mourño, as interior secretary in order to foster better relations with Congress. Mourño was almost immediately assailed for allegedly steering Pemex contracts toward a family firm while serving in other government positions earlier this decade. He was eventually cleared of any improprieties, but his role as a mediator was damaged.

The PAN later sacked party Senate leader Santiago Creel in May to give a new “push” to energy reform proposals that appeared stalled. Analysts say that energy reform simply provided a pretext for replacing Creel, who had a history of butting heads with Calderón and angered the party leadership by accepting a debate challenge on petroleum issues from López Obrador.

PRD: WINNERS AND LOSERS

Energy reform arrived in the Senate mere weeks after the PRD staged a messy internal election, which was eventually annulled by the electoral tribunal. PRD officials spoke of finding unity in rallying against energy reform, but it never really materialized as party moderates disagreed with staging a congressional takeover and avoided participating in López Obrador’s “petroleum defense movement.”

The PRD eventually pitched its own proposals and its members of the Senate Energy Committee take credit for achieving the removal of the provision awarding incentive-laden contracts to Pemex contractors. But López Obrador refused to back the final outcome achieved late last month.

Analysts say the former presidential candidate’s politicking could backfire and strengthen his internal opponents.

“The anti-López Obrador faction … by putting their mark on the reform, they delivered a blow to López Obrador,” said Muñoz of the Universidad Iberoamericana.

“They landed a strong blow to the mobilizations that he leads. His image remains marginal ... and damaged. López Obrador lost his ability to steer the legislative agenda.”

OTHER PLAYERS

The nation’s five small political parties split on energy reform, with the Convergence party and Labor Party – staunch López Obrador allies – voting against the measure. The Green Party claimed victory for having measures included that promote energy conservation and foment the use of renewable sources of energy.

Muñoz commented that many in the business class with PAN ties would come out as winners due to the expanded role for the private sector. Estévez from ITAM agreed.

“The big winner will be all those little Mexican firms,” he said.

“The next best thing to a government bailout is a government contract. It’s just about business patronage."

25 October 2008

Senate votes for reform

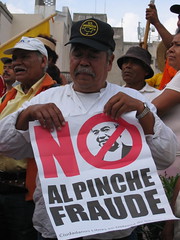

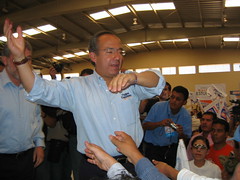

AMLO addresses followers at November 2007 rally.

Senate votes for reform

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

The Senate approved an energy reform package Thursday, six months after President Felipe Calderón unveiled his controversial plan for overhauling the state-run petroleum sector and stemming a precipitous decline in oil production.

Lawmakers from the three main parties voted overwhelmingly in favor of the seven initiatives comprising the package, which now moves to the Chamber of Deputies.

"It's a success that we've had a civilized Senate debate, producing new rules of the game for a better, more modern and more transparent Pemex," said Sen. Manlio Fabio Beltrones, leader of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, in the Senate.

The vote was moved from the Senate chamber to a heavily guarded office tower several blocks away in order to avoid protesters loyal to former presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has long decried the plan as a first step to privatizing the nation's oil industry.

But López Obrador's protests, which included a takeover of Congress earlier this year and regular street demonstrations by his "oil defense brigades," lost some of their steam after members of his same Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, opted to negotiate the deal with the PRI and Calderón's National Action Party, or PAN.

The initiatives approved Thursday grant Pemex increased budgetary and operational autonomy; allow the state-owned oil giant to partner with private firms for oil exploration and exploitation ventures; make the company's tendering process more flexible and provide incentives to restart dormant drilling activity in mature oil fields.

But the reforms discarded Calderón's proposals for paying performance bonuses to Pemex's private-sector partners and eliminated another for building new refineries with private money. The reforms also failed to touch the influential oil workers union, which holds five seats on the Pemex board.

Despite the changes, Calderón lauded the Senate-approved package.

"Without exaggerating, I can say that it is the most favorable change in the hydrocarbons sector since 1938," he said, referring to the year the petroleum industry was expropriated.

Analysts described the reforms as an improvement over the status quo, but inadequate for solving the managerial issues in Pemex and arresting production declines.

"This reform is important in providing Pemex with increased autonomy, both financially and operationally," said Alejandro Schtulmann, director of research at Empra, a Mexico City risk consultancy.

"But it falls short in solving Pemex's challenges. The union is a huge problem ... it won't do anything to reverse the decline of [the massive Cantarell oil field.]"

The vote followed six months of discord over energy reform, which has provoked legislative shutdowns, more than two months of public hearings, a partisan citizen consultation process and the threat of López Obrador-sponsored brigades flooding the streets.

A small group of senators representing a coalition of left-wing parties known as the FAP voted against the reforms due to the lack of a clause explicitly forbidding future privatization. They also objected to a measure allowing private firms to win contracts for managing entire production areas on behalf of Pemex.

Deputy Javier González Garza, PRD leader in the Chamber of Deputies, said the two measures would be raised during debate in the Chamber, although he added, "I agree with a large part of the reform."

Debate in the Chamber is expected to begin Tuesday.

05 October 2008

Guerrero´s Sunday votes a litmus test for governor

Guerrero´s Sunday votes a litmus test for governor

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

Residents of the southern state of Guerrero head to the polls on Sunday in legislative and municipal elections. But rather than being just your run-of-the-mill local political process, the elections are shaping up as a referendum on Gov. Zeferino Torreblanca´s administration <00AD>- and even one on his Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, itself.

Torreblanca rode to power in 2005 on a wave of discontent that also swept the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, out of office after 75 years of oppressive rule in the impoverished state.

The Acapulco retailing magnate ran for PRD on an agenda of change in what is one of the republic´s most marginalized, underdeveloped and conflictive states - a place where 40 percent of the homes have dirt floors, 42 percent of the population is illiterate and the murder rate is double that of the national average, according to federal government statistics.

"The election of Zeferino Torreblanca was historic," said human rights lawyer Mario Patrón, who worked in the La Montaña region of Guerrero until recently.

"After more than 75 years of PRI rule, the civil society took to the streets and voted. There were high expectations," Patrón said.

Guererro residents overwhelming opted for turfing the long-ruling incumbent party - not unlike what had occurred on the federal level five years earlier - in a result that one national broadsheet welcomed as, "Moving toward the end of the outlaw Mexico."

But local observers say that the initial euphoria diminished quickly, as few of the expectations that people had - corruption being reduced, education and social programs being fixed, and oppressive governance being stamped out, for instance - began to materialize.

"They´ve just reproduced the same old practices and the same governing policies," Patrón said. "What we have is power being alternated. There´s been a change of colors, but there has not been a transition."

Ironically - but perhaps unsurprisingly, given the left-wing PRD´s divisions stemming from internal elections both nationally and in Guerrero earlier this year - many of the ballots that could be cast against the PRD are expected to come from disaffected party members, who differ with the governor on policy and party politics.

Some in the PRD predict a humbling at the polls for their party, which is expected to lose seats in the state legislature and could lose numerous municipal races - perhaps most embarrassingly in Acapulco, the state´s largest municipality.

"There´s no possibility of the PRD keeping its majority in the legislature," Alvaro Leyva Reyes, a former campaign coordinator for Torreblanca, told the newspaper El Universal.

TOUGH COMPETITION

Making things even tougher, the PRD is now battling a rejuvenated PRI that has been winning local-level elections nationwide over the past two years, and has shown unity in Guerrero after previously being torn apart by infighting there.

Torreblanca, meanwhile, has drawn the ire of some factions of his party for not adequately financially supporting Andrés Manuel López Obrador´s alternative government, as well as working cooperatively with the PAN administration of President Felipe Calderón.

Torreblanca also has butted heads with the PRD mayor of Acapulco, Félix Salgado Macedonio, according to José Luis Rosales, director of the Rural Development Institute at the Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero.

Salgado has accused Torreblanca of sending that municipality inadequate resources for social programs and urban development projects and described the governor as "PANísta to the core," according to Rosales.

With the PRD stumbling, political observers predict a strong showing from the PRI, which sent its big guns to campaign in Guerrero.

Party president Beatriz Paredes and State of Mexico Gov. Enrique Peña Nieto both made appearances. In Acapulco last Sunday, Paredes described the PRI as united and agents of change.

Patrón, the human rights lawyer, expressed skepticism over the PRI´s pledges to carry out change, but acknowledged that the party was on the rebound in his state.

"The PRI is in the process of reconstruction, and it´s most likely that it will win various municipal governments [in Guerrero]," he said. "It´s starting to regain ground, but this isn´t a result of PRI policies. It´s a consequence of the image of poor governance by the PRD."

07 September 2008

Guadalajara rector spat highlights power struggle

Photo by Steven H. Miller

Guadalajara rector spat highlights power struggle

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

The University of Guadalajara ousted its rector Aug. 29 over vague allegations of mismanagement, sparking calls for campus demonstrations, a string of appeals and accusations of power-brokering at the nation's second-largest public university.

On Aug. 29, Rector Carlos Briseño was ousted by the university's governing council, a body packed with loyalists of Raúl Padilla, a controversial former student leader and rector who is considered by many to be the most influential figure in the university over the past 25 years.

Within hours, Marco Antonio Cortés, a Padilla ally, began occupying Briseño's office in the school's white marble rectory building.

Briseño, too, had once been a friend of Padilla, but after he began cozying up to the local governing National Action Party, or PAN, and the leading opposition Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, both of whom had long been at odds with Padilla, he quickly fell out of favor.

"Carlos Briseño arrived [in the rector's] office by the decree of Raúl Padilla, but the strongman made a mistake," said El Universal columnist Jorge Zepeda, a former editor of the Guadalajara newspaper Siglo 21.

But Briseño wouldn't roll over and play dead, despite decisions by Jalisco Gov. Emilio González and the Public Education Secretariat not to intervene in the case. Instead, he immediately denounced his firing as illegal and began pleading his case to the citizens of the western state.

He convinced a local court to grant an injunction against the firing, but it was overturned Sept. 4 by a federal judge.

Meanwhile, back on campus, 1,500 sympathetic students and teachers in his support on Sept. 5, some of them chanting: "Out with the Padilla crowd!"

OLD-STYLE LEADERSHIP

Briseño assumed the post of rector in early 2007, and it did not take long before he was losing favor with his former mentor.

In late August, Briseño began suggesting reforms at the Centro Cultural Universitario, which oversees a group of successful businesses and projects including hotels, language schools, a burgeoning film festival and the prestigious International Book Fair - the second-largest event of its kind in the world.

Many of the projects had been founded by Padilla, and he had remained as the head of the center after stepping down from the rectory in 1995 at the end of a six-year term.

When asked in an Aug. 28 radio interview why the center and Padilla's leadership of it were being scrutinized, Briseño responded: "Absolute power corrupts.

"I don't have any proof, but we're investigating . we're going to audit each one of the university's businesses," he said.

The General University Council sacked Briseño a day later, citing budgetary mismanagement and insubordination.

For some observers, the firing showed how the university, despite its reputation as an institution on the vanguard of higher education, at the same time remains wedded to an old-style authoritarian leadership.

"At this university, both the past and present are very much alive," said Sergio Aguayo, a professor at the Colegio de México and a Jalisco native.

"There are parts that are excellent, but very large parts are extraordinarily backward in their political culture."

`A BENIGN STRONGMAN'

Zepeda, a University of Guadalajara graduate, called Padilla, "a benign strongman," whose use of power has been both "favorable and unfavorable."

Under Padilla's guidance, both as rector and behind-the-scenes playmaker, the school undertook modernization initiatives that included decentralizing power to regional centers beyond Guadalajara, and organizing successful cultural events.

"In many ways, it's been more at the [cultural forefront] of any other university of the country, including UNAM," Zapeda said.

But the U. de G. - as the school is known locally - has also been viewed suspiciously due to a lack of transparency in its finances. And the school's not-so-secret affiliation with the local Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, which is headed by Padilla, also raised local hackles.

Briseño brought differing political allegiances to the Padilla inner circle. He was openly friendly to the PRI and numerous PRI functionaries, including Gov. Mario Marín of Puebla, Nayarit Gov. Ney González and party president Beatriz Paredes, attended his annual state of the university address in April 2008.

Local newspapers called the annual state of the university address "A coming-out party" for Jalisco's most prominent PRIísta.

Then, when he began forging better relations with the local PAN administration, which had previously denounced the U. de G. for a lack of transparency, he really fell out of favor.

"He had a series of political commitments, with political forces, that were inconvenient for the university . [including] the old national PRI," Zepeda said. "Briseño suddenly represented the possibility of breaking [the U. de G.] open, but for the worst reasons.

"Everyone views it as a jackpot."

30 August 2008

Average citizens suffer horrors of kidnapping, too

The News

Pedro Fletes, a Mexico City teacher and father of six, was pulled from his 1994 Ford Escort by five kidnappers as he passed through the Colonia Roma on a winter morning seven years ago.

His abductors brought him to a "safe house," blindfolded him and kept him confined to a closet for nearly two months. A chain was attached to his leg every night.

Feletes subsisted on a diet of tea and pastries, but was also extended a surprising number of courtesies, including packs of Raleigh cigarettes, his preferred brand.

"If I had been an addict, they would have found me drugs," Fletes said, explaining that his captors treated him like "merchandise" that required care and attention. "The most important thing for them was taking care of me."

Yet in the high-stakes crime of kidnapping, the same captors who brought him his favorite cigarettes might just as easily have cut off an appendage, or even killed him, had the deal for his ransom gone wrong.

Instead, his ordeal ended with him being dumped - penniless and wearing the same clothes he had on when he was grabbed 59 days earlier - at an unfamiliar street corner in a working-class neighborhood near the airport. His family had paid the ransom, the sum of which he declined to disclose, except to say that it was a mere fraction of the millions of dollars demanded by kidnappers involved in high-profile abductions.

Fletes' kidnappers nabbed him for purely economic reasons - even though his salary from his job at a private high school pays him only a middle-class salary. But his abduction came during the early years of a trend in Mexico's lucrative kidnapping industry that has seen the middle and working classes become targets as well as the rich.

"In the '90s and early 2000s, a lot of these kidnappings were done by professionals, groups that were very sophisticated," said Ana María Salazar, a Mexico City political analyst and security expert. "They would plan ahead: who they would kidnap and how much money they were going to get.

"Now people are basically getting kidnapped if they have a nice car or they're wearing a watch, or for some reason there's a perception that they have cash available," she said.

Security experts and the leaders of public security advocacy groups say that the problem for the middle and working classes has only become worse since Fletes was apprehended in 2001. Kidnapping is now so widespread that even impoverished rural villages are feeling its impact.

"There are kidnappings for just 5,000 pesos," said Joaquín Quintana, leader of the anti-crime civic group Convivencia sin Violencia, of the situation in rural areas.

"There are kidnappings where they take a family's child . and ask for a cow and two pigs."

MEDIA ATTENTION

Kidnappings are up 9.1 percent this year in Mexico, averaging 65 per month nationwide, according to the Attorney General's Office. Citizens' groups, however, say that most crimes go unreported, and the real kidnapping rate is likely more than 500 per month.

It's a crime that affects people of all socioeconomic groups. Yet the trend of middle- and working-class kidnappings has been given scant attention by the national media, which this month has focused heavily on the plights of two wealthy families, whose children fell into the hands of kidnapping gangs.

Fernando Martí, whose father Alejandro Martí founded a sporting goods retail empire, was found dead in the truck of an abandoned car July 31. His parents had reportedly paid a $5 million ransom, but it failed to save their 14-year-old son.

The mother of Silvia Vargas made an emotional plea for her daughter's return last week along with offering a reward and posting a billboard to flush out information on the kidnapped 19-year-old, whose father previously ran the National Sports Commission.

The plights of both teenagers made the front-page headlines.

"What happens is that when it's someone from the upper class, and it's a well-known person, it appears in the press," Quintana said.

In the Martí case, the extensive press coverage fomented immense public outrage. A massive march against kidnapping is now planned for Saturday evening in downtown Mexico City.

The coverage also prompted political action - and public displays of support from the country's most prominent politicians. President Felipe Calderón attended the funeral Mass for the 14-year-old kidnapping victim. The president, all 31 governors and the mayor of Mexico City also convened a security summit last week, where the leaders agreed to a 74-point action plan after receiving a public tongue-lashing from Alejandro Martí.

In an apparent reference to the Martí case, Attorney General Eduardo Medina Mora acknowledged that "perhaps it takes emblematic events to make us realize that the government is far from living up to its obligations."

But some have suggested that class interests are what drive the government's and public's concern for kidnapping. Back in 2004, then-Mexico City Mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a self-styled champion of the poor and working classes, branded the backers of an anti-kidnapping protest as "spoiled rich kids."

`AN INCREDIBLE BUSINESS'

Security experts say the kidnapping industry began taking off in the mid-1990s, a time when the peso collapsed and authoritarian one-party rule came to an end on the national and Mexico City levels. Asked to explain kidnappings of working-class people, experts cite reasons ranging from lax law enforcement and deteriorating economic conditions to efforts by the rich to make themselves more difficult to apprehend by purchasing bulletproof vehicles and hiring private security.

Perhaps most important of all, the kidnapping of the middle and lower classes, especially in volume, can be a highly lucrative activity.

"There are gangs that do a lot of small-time kidnapping, because these types of kidnappings are a good business," Quintana said.

"There are no complaints filed, nobody goes after anybody. It's an incredible business."

A flood of new entrants changed the industry by carrying out both express kidnappings, in which the victims are forced to simply empty their bank accounts, and virtual kidnappings that trick victims via the telephone into thinking that their loved ones have been apprehended.

Traditional kidnappings are also becoming less sophisticated as victims are increasingly being mutilated and killed, according to Quintana.

"What we're seeing now, unlike before, is that there are no longer any ethics," he said.

"Before, if they were professionals, they would kidnap [the victim] and treat them like merchandise - take care of them, feed them well, return them in good condition. What's happening now is that you pay for the rescue and [the victim] is murdered."

Fletes, who now runs a support organization for the families of kidnapping victims, expressed gratitude that his kidnappers were of the professional variety.

But the reason he was ever targeted in the first place still mystifies him.

"I'm not a rich man," he said.

25 August 2008

The untouchables

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

Omar Toledo Aburto normally mans one of the offshore rigs pumping crude from the Campeche Sound. But these days, he's in charge of a protest camp outside the Labor Secretariat, where he sleeps in the cab of a pickup truck parked alongside one of the capital's busiest thoroughfares.

But his current discomfort has nothing on the possible consequences of confronting the powerful oil workers union, which represents more than 90,000 Pemex employees nationwide, and is run by a group that "rules through terrorism," as Toledo Aburto puts it. "If you don't agree with their rules, you'll automatically be fired," he said.

Or, worse, subjected to death threats and harassment.

Mere hours after the 24-year-veteran petroleum worker set up camp in Mexico City on July 28, his wife and children were threatened by "union toughs," he said. But even though he expressed concern for his family's safety, he remains defiant.

"I'm not scared," he said, pointing to a property line marking the limits of the guarded federal land that he's currently occupying.

With the nation's political parties immersed in debates over proposed reforms to the nation's oil industry, Toledo and a band of about a dozen current and former Pemex workers are calling for changes in the oil workers union, an organization that wields enormous influence over the state-owned petroleum concern, Pemex, and dominates the political sphere in many oil-producing parts of the country.

But such is the union's clout that neither the governing National Action Party, or PAN, nor the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, has dared propose altering the union's relationship with Pemex in their energy reform proposals. Interior Secretary Juan Camilo Mouriño recently said that dealing with the union "is a different discussion," while PRI senators approved a measure last week saying that they would only support an energy reform package that omits union changes. "People pay tremendous prices for fooling with the union," said George Baker, a Houston-based energy consultant and expert on the Mexican oil industry.

Only the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, which plans to unveil its own energy reform initiative on Monday, has dared to challenge the union, which some analysts say is a foe of the left-wing party.

"For the PRD, the oil workers union is a political enemy," said Aldo Muñoz, a union expert at the Universidad Iberoamericana. "The Pemex union supports the PRI and, if it suits them, PAN candidates against the PRD."

PRD Sen. Carlos Navarrete last week warned that the PRD would recommend stripping power from the union in its energy reform proposal.

"In what part of the world does the union have almost half of the [seats on the] board of directors in the most important company in its country?" Navarrete told the newspaper Excélsior. "It's absolutely anachronistic."

Former PRD presidential candidate López Obrador has gone even further, accusing the government and the oil workers of brokering an unseemly, but mutually beneficial, deal.

"There's an agreement between [oil workers union leader] Carlos Romero Deschamps and [President] Felipe Calderón to keep corruption in the union in exchange for supporting the Calderón reform," he said recently.

Some analysts, meanwhile, question whether tackling the union issue - however worthwhile an objective - is appropriate during the early phases of a politically difficult reform process.

"You're trying to get some initial traction [on reform]," Baker said. "Getting traction on the union question probably isn't at the top of the list."

The union, too, has remained silent on the government's energy reform proposals - which would allow increased private sector participation in the exploration and exploitation of oil reserves - a move that Muñoz said was symbolic of just how "pragmatic" the syndicate is.

"It publicly supports the PAN in terms of energy reform, because its interests are never touched," he said.

THE PATH TO POWER

The origin of the oil union's power goes back decades. It initially gained authority after the 1938 expropriation of the petroleum industry, as then-President Lázaro Cárdenas proposed having the government and workers co-manage Pemex. That arrangement established conditions for the union leader to play an important role on the national stage, while his subordinates dominated the affairs of regional petroleum centers, where they funded public works projects, held sway over municipal governments and often ran local businesses.

Even to this day, section leaders control hiring and firing decisions. Nepotism is said to be rife, and positions are reputedly sold for as much as 50,000 pesos. (Pemex could not be reached for comment on these allegations, but has denied them in the past.)

Union leaders often manage side businesses that provide Pemex with employee transportation services, construction crews and basic supplies, according to the dissidents protesting in Mexico City. The union also holds five of the 11 seats on the Pemex board of directors.

Oil workers are now some of the best-paid employees in the country, as the union has consistently won generous wage and benefits packages that include gasoline subsidies, a series of worker-only hospitals and Christmas bonuses worth nearly two-months' pay.

The wealth and influence of the union leaders and members - "the real sheiks" of the oil industry, as Alan Riding called them in his 1985 book on Mexico, "Distant Neighbors" - are far-reaching, too. Successive governments have yielded to the union's hardball negotiating tactics, which have included the trump card of threatening to shut down the entire petroleum sector - the source of 40 percent of the federal budget.

BATTLING ON

Allegations of thuggery - denied by the company - are also common. Toledo said that at least 80 dissident members have disappeared over the past eight years.

The union dissident is calling for Romero Deschamps to be deposed by the Labor Secretariat, arguing that the date of the last internal election was improperly moved ahead.

"He's interested in nothing more than keeping himself in power," Toledo Aburto said. "This man, in every sense of the word, has hijacked the union."

In spite of the threats, the union protesters plan to stay put - partly out of principle, but also due to the potentially uncomfortable situation that awaits some of them upon returning to their hometowns and workplaces.

"I can't go back," Toldeo Aburto said. "They've already stripped me of my job."

The Untouchables

Even with energy reform on political agenda, few dare address a core issue: Pemex's union

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

Omar Toledo Aburto normally mans one of the offshore rigs pumping crude from the Campeche Sound. But these days, he's in charge of a protest camp outside the Labor Secretariat, where he sleeps in the cab of a pickup truck parked alongside one of the capital's busiest thoroughfares.

But his current discomfort has nothing on the possible consequences of confronting the powerful oil workers union, which represents more than 90,000 Pemex employees nationwide, and is run by a group that "rules through terrorism," as Toledo Aburto puts it. "If you don't agree with their rules, you'll automatically be fired," he said.

Or, worse, subjected to death threats and harassment.

Mere hours after the 24-year-veteran petroleum worker set up camp in Mexico City on July 28, his wife and children were threatened by "union toughs," he said. But even though he expressed concern for his family's safety, he remains defiant.

"I'm not scared," he said, pointing to a property line marking the limits of the guarded federal land that he's currently occupying.

With the nation's political parties immersed in debates over proposed reforms to the nation's oil industry, Toledo and a band of about a dozen current and former Pemex workers are calling for changes in the oil workers union, an organization that wields enormous influence over the state-owned petroleum concern, Pemex, and dominates the political sphere in many oil-producing parts of the country.

But such is the union's clout that neither the governing National Action Party, or PAN, nor the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, has dared propose altering the union's relationship with Pemex in their energy reform proposals. Interior Secretary Juan Camilo Mouriño recently said that dealing with the union "is a different discussion," while PRI senators approved a measure last week saying that they would only support an energy reform package that omits union changes. "People pay tremendous prices for fooling with the union," said George Baker, a Houston-based energy consultant and expert on the Mexican oil industry.

Only the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, which plans to unveil its own energy reform initiative on Monday, has dared to challenge the union, which some analysts say is a foe of the left-wing party.

"For the PRD, the oil workers union is a political enemy," said Aldo Muñoz, a union expert at the Universidad Iberoamericana. "The Pemex union supports the PRI and, if it suits them, PAN candidates against the PRD."

PRD Sen. Carlos Navarrete last week warned that the PRD would recommend stripping power from the union in its energy reform proposal.

"In what part of the world does the union have almost half of the [seats on the] board of directors in the most important company in its country?" Navarrete told the newspaper Excélsior. "It's absolutely anachronistic."

Former PRD presidential candidate López Obrador has gone even further, accusing the government and the oil workers of brokering an unseemly, but mutually beneficial, deal.

"There's an agreement between [oil workers union leader] Carlos Romero Deschamps and [President] Felipe Calderón to keep corruption in the union in exchange for supporting the Calderón reform," he said recently.

Some analysts, meanwhile, question whether tackling the union issue - however worthwhile an objective - is appropriate during the early phases of a politically difficult reform process.

"You're trying to get some initial traction [on reform]," Baker said. "Getting traction on the union question probably isn't at the top of the list."

The union, too, has remained silent on the government's energy reform proposals - which would allow increased private sector participation in the exploration and exploitation of oil reserves - a move that Muñoz said was symbolic of just how "pragmatic" the syndicate is.

"It publicly supports the PAN in terms of energy reform, because its interests are never touched," he said.

THE PATH TO POWER

The origin of the oil union's power goes back decades. It initially gained authority after the 1938 expropriation of the petroleum industry, as then-President Lázaro Cárdenas proposed having the government and workers co-manage Pemex. That arrangement established conditions for the union leader to play an important role on the national stage, while his subordinates dominated the affairs of regional petroleum centers, where they funded public works projects, held sway over municipal governments and often ran local businesses.

Even to this day, section leaders control hiring and firing decisions. Nepotism is said to be rife, and positions are reputedly sold for as much as 50,000 pesos. (Pemex could not be reached for comment on these allegations, but has denied them in the past.)

Union leaders often manage side businesses that provide Pemex with employee transportation services, construction crews and basic supplies, according to the dissidents protesting in Mexico City. The union also holds five of the 11 seats on the Pemex board of directors.

Oil workers are now some of the best-paid employees in the country, as the union has consistently won generous wage and benefits packages that include gasoline subsidies, a series of worker-only hospitals and Christmas bonuses worth nearly two-months' pay.

The wealth and influence of the union leaders and members - "the real sheiks" of the oil industry, as Alan Riding called them in his 1985 book on Mexico, "Distant Neighbors" - are far-reaching, too. Successive governments have yielded to the union's hardball negotiating tactics, which have included the trump card of threatening to shut down the entire petroleum sector - the source of 40 percent of the federal budget.

BATTLING ON

Allegations of thuggery - denied by the company - are also common. Toledo said that at least 80 dissident members have disappeared over the past eight years.

The union dissident is calling for Romero Deschamps to be deposed by the Labor Secretariat, arguing that the date of the last internal election was improperly moved ahead.

"He's interested in nothing more than keeping himself in power," Toledo Aburto said. "This man, in every sense of the word, has hijacked the union."

In spite of the threats, the union protesters plan to stay put - partly out of principle, but also due to the potentially uncomfortable situation that awaits some of them upon returning to their hometowns and workplaces.

"I can't go back," Toldeo Aburto said. "They've already stripped me of my job."

29 July 2008

Citizens consulted on oil

Former Mexico City mayor Alejandro Encinas casts a ballot in a non-binding referendum on energy reform promoted by opponents of the plan.

By DAVID AGREN

The News

Residents in the capital and nine states weighed in Sunday on the future of the country's petroleum sector by casting votes in a non-binding referendum sponsored by a coalition of left-wing political parties.

A Consulta Mitofsky exit poll showed more than 80 percent of respondents voting "No" on the two questions, which asked if private companies should participate in the oil industry and if the lawmakers should approve the energy reform legislation submitted in early April by President Felipe Calderón.

Mexico City Mayor Marcelo Ebrard of the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, unveiled the referendum two months ago as a means of derailing Calderón's plan to expand private sector involvement in the country's petroleum sector and grant the state-run oil concern Pemex more autonomy.

The consultation, or "consulta," initially captured significant media and public attention, but the buzz diminished as the capital government began dealing with public dissatisfaction over the handling of a botched nightclub raid and the PRD was forced to annul its internal election due to widespread vote tampering and allegations of dirty tricks.

Still, organizers anticipated that up to five million people nationwide would participate in the consultations, which are scheduled to be carried out in three stages through Aug. 24.

Voters began trickling into the nearly 4,400 polling stations around the capital at 8 a.m. Brigades of promoters petitioned passersby to participate, but turnout appeared light.

"It's just like the presidential election - the whole thing has already been decided," said parking attendant Roberto Pascual, who abstained from voting.

Polling stations outside of Mexico City reported even lower turnouts.

"People are really apathetic," said Guillermo Aguilar, a government employee manning a Coyoacán polling station.

"The whole thing has been discredited by the press," he added.

Some press reports said that employees in the local government were pressured into working the consultation, but Aguilar said that he willingly volunteered and only received a T-shirt, ball cap and box lunch in exchange for his services.

Consultation participants were required to show a valid voter identification, but ballots were marked with a black crayon in plain sight of the polling station workers.

City social worker Fernando Najera voted "No" on both questions, saying the Calderón plan was "privatization ... but they just gave it a different name."

21 July 2008

Annulment solves little for PRD

Annulment solves little for PRD

BY DAVID AGREN

The News

The two frontrunners in the Democratic Revolution Party´s internal election on Sunday blasted an internal decision to annul the party´s March 16 leadership vote, setting the stage for more factional infighting at the nation´s largest leftist party.

Candidate Jesús Ortega, the front man of a pragmatic faction known as the New Left, said that the party known as the PRD "is shooting itself in the foot" by annulling the election that he had led by 16,000 votes over rival Alejandro Encinas.

"With this, it´s only causing damage to the PRD and bringing about further discredit in the eyes of the media and the public," he added.